What pet owner hasn’t at some point looked into the face of their furry little chum and wondered what it’s thinking? Wouldn’t it be great to be like Dr Doolittle, to imagine “chatting to a chimp” and being able to “curse in fluent kangaroo”? Of course, as Gary Larson points out in one of his cartoons, even if this were possible, the reality may not be all that we hope. Yet if Elon Musk continues along his Bond-villain trajectory, then it may not be long before we can read human thoughts – and if human, then why not animal?

But not everyone is so hopeful. The Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once stated that “if a lion could speak, we could not understand him”. This seems an odd thing to say. Does the king of the beasts have a particularly thick Lionese accent? Does he mumble? Are his sentences an impenetrable slew of jungle jargon? Ha ha. Ha. No. Wittgenstein’s point is that, as species, lions and humans are so different in kind, we live such different “forms of life”, that even if a lion could express itself in words, those words would not have the same significance for us and for him. This is because words aren’t merely labels for ideas; they are sounds and symbols that form part of a deep and complex social pattern. A word isn’t just a dictionary definition, but brings with it feelings, values, norms of behaviour, assumptions concerning the way the world is, etc. Think of the word “parent”, and all it tells us about the way humans are, our biological nature, our family values, and so on; then think what that word might mean for a lion. There are similarities, of course, but there are also huge differences. And it is those differences that would make it practically impossible for us to fully comprehend Lionese – and for him to understand human discourse, too.

You may disagree with this. But haven’t we taught chimps sign language? Wasn’t there that horse that could count? And wasn’t Lassie able to tell us that Timmy was stuck down the well? Isn’t the mere fact that your cat can nudge your elbow, and thereby tell you that it’s hungry, proof that human-animal communication is possible? Well, yes – to a limited degree (though I think they worked out the counting horse thing was a scam, and, for crying out loud, who knows WHAT the cat ACTUALLY WANTS?). But Wittgenstein’s point is that language is an expression of all that we are, and since humans and animals are so different, then full communication between them (à la Dr Doolittle) must remain the stuff of Disney’s dreams.

All of which brings me on (naturally) to computers. Does Siri understand you? Will Alexa one day be capable of having a genuine debate? I would say not. And this isn’t just because computers are very different from us, but because the way in which computer programmers are currently attempting to create thinking machines will never produce one. First of all, Siri and Alexa do not “think”; they merely parrot back something from a range of pre-programmed responses. If you mention “the weather”, then it will cross reference this with information on where you live, data from the Met office, and so on, before saying, “Today in London will be cloudy, with a high of 10 degrees”. If you say, “Siri, what’s the meaning of life,” then it will draw from its stock of witty one-liners that some human has sat down and written (and not a particularly witty human, in my experience). Even the further (and quite startling) advances in AI with ChatGPT, etc, do not constitute “thinking”, in its fullest sense, for the AI’s responses are probabilistic: they trawl huge amounts of data and create a response deemed most likely to fit the context of the conversation.1 But this doesn’t rule out various types of misunderstanding, self-contradiction, and simple falsity.

But secondly, even if there were a way to create computers that could think and communicate as humans do (what is termed “artificial general intelligence” or AGI), would this result in meaningful conversations with machines? Wittgenstein would say, arguably not. This is because the deeper things that underlie communication – feelings and emotions, values, relationships, assumptions, etc – are not capable of being programmed into a computer, for they are either unquantifiable, or are so many that we are not even aware of them ourselves.

Our grasp of the world is largely intuitive and unconscious. From being tiny infants, we pick up knowledge of our environment that we are not explicitly aware of, and that we may never have been taught – that cats don’t fly, that bees are not capable of teleportation, that apples can’t speak Mandarin. But for a computer to make sense of even a simple sentence, for it not to get caught out with an embarrassing faux pas, these things would have to be deliberately programmed in. And how could they be? This is not to say that our background knowledge of the world is correct, of course, but that such a set of background assumptions is necessary in order to make sense of the simplest utterance.

The startling success of AI might be cited as an objection to the above. If we ask ChatGPT whether cats can fly, or apples talk, then it will of course say no. But such successes do no more than obscure the problem – and there is no shortage of AI faux pas. For instance, one of Microsoft’s AIs generated a poll inviting readers to speculate on the cause of the death of a woman in an accompanying news article; a group of Australian academics used Google Bard to generate allegations against consulting companies, which turned out to be made up.2 The point is that, as impressive as AI seems to have become, there are still quite alarming and very basic gaps that are revealed in the way it “thinks” – often simple mistakes that a human would not make.

As AI developer Steven Shwartz has argued, AI lacks “common sense” – a basic grasp of the world that underpins all their actions and communications – and always will do. But couldn’t a computer infer such background knowledge from a particular set of facts? From the fact that apples don’t possess speech organs and cats have no wings? Possibly, to an extent, but even if it could, such facts are only part of the background (and since arguably a machine could never be conscious or have feelings, then this would seem to rule out it acquiring those emotions and other qualitative states that also form part of this background). All of which ultimately seems to suggest that AGI is about as likely as a talking lion.

And what about lions? Do they have common sense? Do dogs and cats? Well, yes, probably, but – judging from my dog and cat, at least – it is likely not anything like our own.

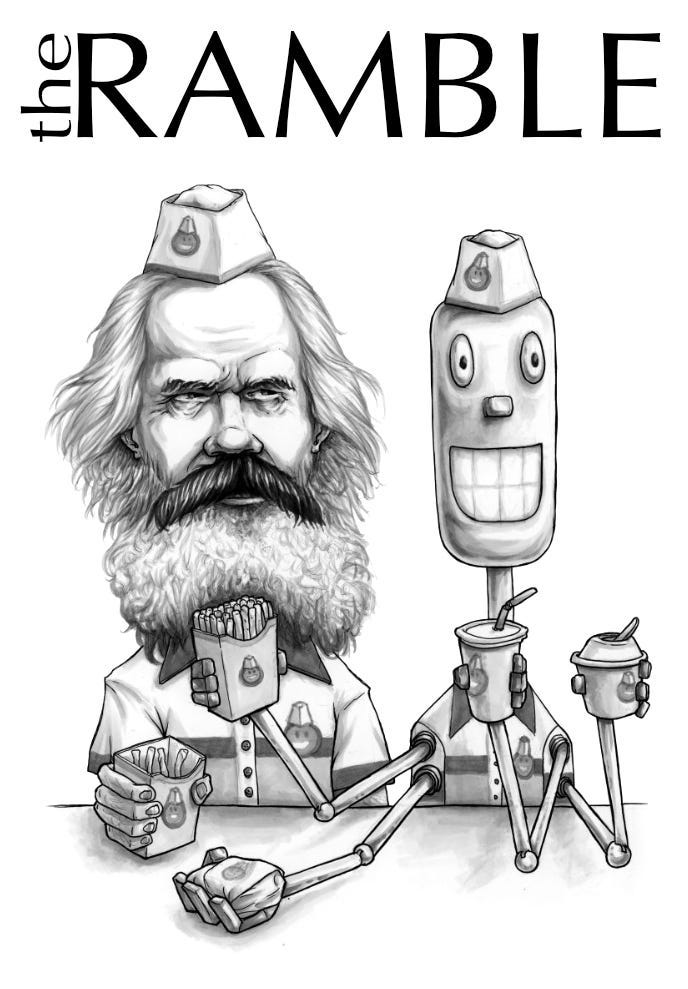

The Ramble represents my occasional musings on things that interest me philosophically – technology, art, science, religion, the facial hair of the great philosophers – free to everyone until the end of time (well, until the end of my time, anyway...).

Obviously, it’s more complicated than this, and there are various evolving models that are refining the basic approach to eradicate the common types of error listed here. However, the basic point still applies: this isn’t “thinking” in the truest sense.

You can see a long list of AI SNAFUs on this very useful website.