Whether or not Hell is a real place, its geography in the popular imagination owes much (indirectly) to philosophy. The basis of this influence is the Greek philosopher Aristotle, and specifically his account of the various reasons for immoral behaviour, which helped furnish the Christian notion of Hell. But before we before we get into that, we must know define what “bad” is, and to do that, we must first understand goodness.

According to Aristotle, a moral action must be deliberately chosen, involving conscious knowledge of what is good. A good action is not just something with a good result, but must involve you having a clear sense of what you’re doing, and why you’re doing it. To accidentally help an old lady cross the street, or for the wrong reason, doesn’t count. It must also spring from the right motives and virtuous instincts. Virtuous adults are likely to be those that have had a sound moral education when growing up: Mummy and Daddy taught them right from wrong, and made sure that they were praised for sharing their toys, and disciplined for sneaking down into the kitchen in the middle of the night to scarf all the cookies and blame it on the dog. In other words, they have developed good moral habits, which is more or less what Aristotle thinks a virtue is: a habit.

OK, now let’s look at immorality.

When things go wrong, morally speaking, it’s therefore either because people haven’t developed the right moral habits (virtues), or else because they lack the correct moral understanding (knowldge). Together, these two criteria give us basically three categories of wrongdoing:

Those who possess moral understanding (they know what good and bad are), but have not developed the right moral habits (virtues). This weakness Aristotle terms akrasia.

Those who have developed the wrong moral habits (their parents or teachers were themselves bad or inept) and the incorrect moral understanding (they are vicious people - i.e. they have developed habitual vices instead of virtues).

Those who have no will power or rational capacity at all, and are almost totally subject to their own irrational desires (what Aristotle calls “brutish”persons – that is, like animals or “brutes”).

Taking the first of these first, akrasia means “incontinence”, which is nothing to do with adult nappies and everything to do with having good intentions – but little else. An incontinent person, in the moral sense, knows what they should do, but lacks the will power, self-control, or well-developed moral habits to follow through on that knowledge. In contrast, the vicious person (i.e. possessing vices) has self-control, but has (through a bad upbringing, bad moral choices, etc) developed both a twisted sense of right and wrong, and bad moral habits. Such people consciously and deliberately choose immorality. The brutish person, however, lacks any sort of reason. These individuals are barely human, and behave like animals (brutes), possessing no restraining rationality.

Of course, all three types of people may only have these characteristics in relation to certain actions – maybe they are only occasionally incontinent, vicious, or brutish. However, since (for Aristotle) virtue is an all or nothing affair, then even partial bad tendencies are enough to poison the whole character; one bad moral habit spoils the whole barrel of (perhaps) otherwise fine qualities.

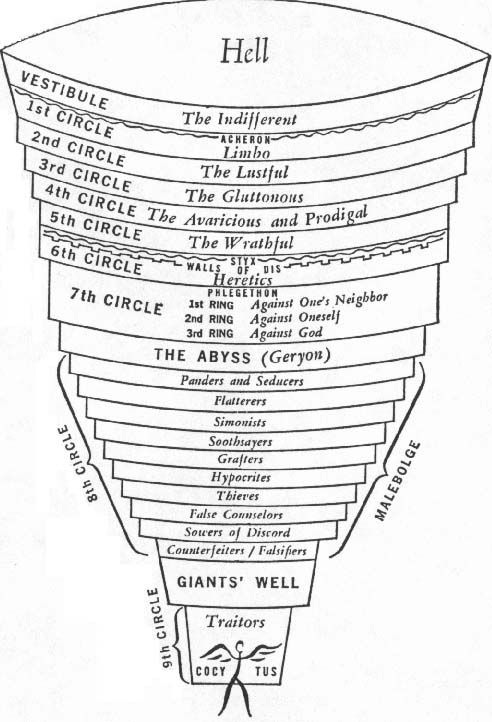

When we come to Christianity, we’ll see that this three-part division has had a huge influence. The Christian vision of Hell has perhaps been most greatly shaped by the medieval poet Dante in his Divine Comedy, specifically the first part or Inferno. Dante was heavily influenced by the theologian St Thomas Aquinas, who was chiefly responsible for applying Aristotelian philosophy to Christianity. So we should not be surprised that the Roman poet Virgil (whom Dante employs as his guide through his visionary journey) specifically references Aristotle, noting that Hell broadly divides into three main areas: the incontinents, the violent, and the malicious:1

Having made this threefold division, Dante further divides incontinence into four (circles 2 to 5): the lustful, the greedy, the hoarders or wasteful, and the wrathful – or, sex, food and drink, money, and anger. "But that's all the good stuff!" you say. Sometimes I worry about you...

The second major division – circles 6 and 7, corresponding to Aristotle’s notion of brutish behaviour – Dante devotes to violence, which you may not think particularly different from anger (wrath), but Dante has some very particular things in mind, such as violence against God (blasphemy), against nature (sodomy), and against the self (suicide). As with Aristotle, Dante sees brutish behaviour as worse than incontinence, but not as bad as vice. Violence is more than just losing your temper, but a debased characteristic that pervades the whole person.

The final two circles (8 and 9) are reserved for the truly wicked: those who have lied, deceived and betrayed. Such behaviour is not the result of momentary impulse, nor even a coarse or brutish nature, but a developed and cultivated form of evil that employs our highest function: rationality. The most wicked sinners are there by coldly calculated conscious choice and have turned God’s greatest gift to humanity against Him.

Along the journey, Virgil points out to Dante the various ways in which the inhabitants of each circle suffer suitably fitting punishments: the lustful and adulterous are blown about by a perpetual wind, forbidden ever to touch those with whom (when alive) they were all too fond of touching; those who deceived by flattery are immersed in a tide of human excrement, as if they now have to live with all the “crap” they spewed during life. In all of these predicaments there is therefore a poetic irony at work, as if the sinners have brought their punishments upon themselves through pursing the sin that condemned them there. This is perhaps more a Platonic notion than an Aristotelian one – that immorality is almost a form of self-harm, for Plato believed that immorality is a disease that inflicts the soul. But Aristotle too makes clear the connection between living morally and living happily, and that therefore to behave immorally is simply a recipe for misery.

But there are also a number of specific tweaks that Dante adds to Aristotle’s moral categories. Heresy is deemed a sin worthy of its own circle, situated between incontinence and brutish violence. There is also, somewhat ironically, a higher circle (cirlce 1, “Limbo”) reserved for “virtuous pagans”, or those wise non-Christians who have lived a virtuous life, but had the misfortune not to believe in the Christian God, or else to be born before the coming of Christ. These individuals are not punished, but nor are they rewarded, the circle's inhabitants merely living in an eternal waiting room. Here are many of the great and noble thinkers, writers, generals, etc, of non-Christian cultures and times, which includes of course the Greek philosophers of antiquity … and thus Aristotle himself.

The Ramble represents my occasional musings on things that interest me philosophically – technology, art, science, religion, the facial hair of the great philosophers – free to everyone until the end of time (well, until the end of my time, anyway...).