Only Us

Or What Marmite Can Teach Us About Immortality, and Myers-Briggs About Mummification

Sometimes, in idle moments, I like to picture my funeral. The tearful faces of loved ones, family, friends, the sombre procession of heartbroken mourners snaking round the block from the … well, I guess they’ll have to hire some sort of hall to accommodate the overflow, or live coverage relayed to screens set up ad hoc in squares and public places. Traffic will grind to a stop, dogs halt their bark, workers will pause from their daily toil and children from their play. At some point in the proceedings, as the last strains of AC/DC’s “For Those About to Rock” fade away, my lovely widow, radiant in her inconsolable grief, will approach the podium.

“He…” – her voice choking with racking sobs – “… he loved Marmite!” She breaks down, unable to go on. But it’s OK – I understand. I was a lot. The loss must be crippling.

(And it’s true. I did (do!) love Marmite. And rainbow cake. And reading in cafes. The cinematic back catalogue of Michael Bay. The works of Mick Herron. Walking our beagle in the woods. Looking for our beagle in the woods.)

But my work is not yet done, for in the background, beneath the grand public spectacle, an unseen drama is playing out. I must perform one last great service to humanity!

She is nineteen, her promising young future as an AI whisperer snatched away as the self-driving SUV blindsides her off her self-peddalling bike. She is in a critical condition, and failing fast. “She needs new heart and lungs,” the doctor informs her distraught parents. “She’s on the transplant list, but it’s in the lap of the gods, now.”

Which is where I come in! Not as a god, no, but celebrated philanthropist that I am, of course I have a donor card! And what’s mine is now hers…

The operation is a success. “She’s coming round from the anaesthetic,” the surgeon tells her anxious parents. “Would you like to see her?”

They enter her room. Already they can see the colour has returned to her cheeks, replacing the ghostly yellow pallor that until recently sat there. She smiles weakly, tries to speak. They lean in closer.

“You know,” she croaks, “I could really go for some Marmite on toast – not spread too thick! And is the next Slow Horses book out yet?”

Of course, most of this is fiction. I’m not really a big fan of AC/DC and have only a passing fondness for the Transformers movies. But the “acquired memory by transplant” bit: that’s true – sort of. Well, it’s true that it may be true.

In 1988, an American woman named Claire Sylvia received the heart and lungs of an 18-year-old male who had died in a motorcycle accident. Subsequently, she developed a taste for beer, KFC and “curvy blondes”! There are other stories of such “acquired” traits, and there may even be some scientific basis for it, but all such evidence remains anecdotal and subject to scepticism. As one commentator points out, the steroids that post-operative transplant patients routinely receive increases the appetite, so it’s no surprise that new tastes begin to emerge. (For curvy blondes…?).

Whether or not such stories suggest the persistence of “cellular memory” I have absolutely no idea, but it did remind me of the fact that cultures throughout history have tended to disagree as to the essential component of the self. When mummifying the dead body in preparation for its journey to the afterlife, the ancient Egyptians preserved the deceased’s heart and lungs in canopic jars, and also occasionally the liver, kidneys, parts of the stomach, intestines, and other internal bits and pieces. However, they considered the brain mere “cranial stuffing”, and simply disposed of it by dragging it out through the nose with a hook.1 Similarly, the Mayans and Aztecs thought the heart to be the centre of life, wisdom and courage. In more modern times, D. H. Lawrence made an impassioned case for the solar plexus: “where you are you … your first and greatest and deepest center of consciousness", where the umbilical chord attached you to the primary source of your existence. Lawrence thought that awareness from this centre thus gives us a more primal and vital connection to life, and that many of the problems of modern society, particularly its attitude to sex, stems from people being divorced from this instinctive life of the “belly”, having developed a separate and partial sense of self as being “in the head”.

“Head” culture seems equally prevalent in our current times, perhaps even more so. When we think of ourselves, we tend to think of our brains – or at least, science does. Futurist Ray Kurzweil is still talking of “merging our brain with the Cloud”, and at times it seems like the Musks and Zuckerbergs of this world want to persuade us that we might live on indefinitely if we just gave them enough access to our personal data (“Immortality? There’s an app for that!”). Cryogenics enthusiasts are only concerned with preserving the brain, because by the time we have the technology to reverse the aging process (and repair the cell damage that results from being kept at -80°C or below), we can simply 3D-print you a whole new body!

This controversy concerning head vs heart (or gut, liver, etc) is therefore, you might think, outdated. It’s the persistence of consciousness and memory that count, and aren’t they situated in the brain? And for us to be the same person as we were before death, then we would also need access to the same memories. And if science can preserve that (cryogenically or digitally), then – assuming your heart doesn’t retain the only record of your fondness for curvy blondes – who cares about the other stuff? After all, as philosopher Antony Flew once asked, what consolation is it to me if “my appendix would be preserved eternally in a bottle”?2

I covered much of this controversy in my PhD, where I argued that the sort of situations we are sometimes presented with in cases of irreversible coma call upon different intuitions as to who and what we really are. For instance, if a coma victim has suffered injury to the brain stem, then they might need artificial assistance to breathe or to regulate their heart rate, but their upper brain function (should they ever reawaken) may be unaffected. In contrast, if the upper brain is damaged, then even though they can breathe, etc, unaided, they may no longer be able to sustain conscious rational thought. But under which of these situations (if either) would we be permitted to consider them “dead”? Some might consider the persistence of the body’s unaided natural functions to be sign enough that they are still “alive”, while others might consider the inability to consciously maintain their sense of self a sign that the “person” has died, and the “living” body is of no consequence. Which we consider more important seems to call upon competing intuitions of who or what a person really is – which is arguably not a question that science itself can resolve for us; it’s about what we value.

You might think that this is only a problem for the non-religious. If I believe in a soul, then it’s not the body (or any particular part of it) that constitutes “me”, but my eternal spiritual essence. But even here, we find similar controversies arising. In Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Little Buddha, an American boy is “recognised” as the reincarnation of a Tibetan lama. However, it then emerges that there are two other boys who have been independently identified as candidates. Eventually, the dilemma is resolved when it is concluded that each boy represents a reincarnation of a different “aspect” of the deceased lama: his body, voice and mind, respectively.

We find other similar examples of this divided self with the ancient Egyptians (the concepts of Ba, Ka and Akh, etc.), Greek philosophy (the Logistikon, Thymoeides and Epithymetikon of Plato), the Jewish Kabbalah (the Nefesch, Ruach and Neshamah), and so on. And even if we opt for a simple division between soul and body, there is still the question of what we will associate with each. Religiously motived French philosopher René Descartes thought that we are simply “thinking things” (rational souls), all passions and desires being merely the influence of bodily stimuli. So what happens when these stimuli are removed? Do they disappear? Do the dead get angry? Sad? Horny? Do they still like Marmite?

So, secular or religious, the controversy seems to persist: who or what are we?

The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung also took a view of the self as divided. Drawing on religion, mysticism and mythology, he broke away from his mentor Sigmund Freud, who had also seen the individual as consisting of warring parts (Id, Ego and Superego). But unlike Freud, Jung saw the purpose of psychoanalysis as not to more efficiently suppress or sublimate our rebellious instincts, but to lead the fragmented person back to wholeness – a process he called “Individuation”.

Jung’s psychology was the inspiration for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a personality test beloved of careers advisors and prospective employers everywhere. But Jung was not really concerned with helping you find out which Harry Potter character you most resemble. The purpose of his scheme was to identify where your imbalance lay. You are an introvert, let’s say, who prefers spending time reading books and eating rainbow cake in cafes, and walking their beagle in the woods. This means that while your intellect and sense of inner worth may be well developed, you are lacking the sort of emotional growth and practical skills that mixing with people and having worldly ambitions might provide. You are one-sided, because there is more than one side to you. You are not just a mental being, but physical, emotional, sexual, spiritual; a being that needs social interaction and meaningful relationships, projects and plans. And if you are ignoring or suppressing these other sides to yourself, what harm might they be unconsciously wreaking? Through anxiety, irrational fears, emotional turmoil, psychosomatic symptoms, all bubbling away beneath your conscious awareness?

We are, as German philosopher Friedrich Nietsche put it, not a single individual, but a “commonwealth”, “composed of many souls”, each of which is a competing “will” and would be master over the others.3 You want to impress a prospective romantic partner, so you decide you need to lose weight, but you also have a passion for marzipan brownies. Which side will win? Like Jung, Nietzsche also wanted to unite the individual, which he saw as the formation of one single “will to power”. This is not the dominance of one overriding aspect (as “power” might suggest), but the cultivation, blending and evolution of all that we are into one unified purpose. That’s it! You will impress your love-interest with your homemade marzipan brownies! (I must move on from examples that involve baked goods and weight loss.)

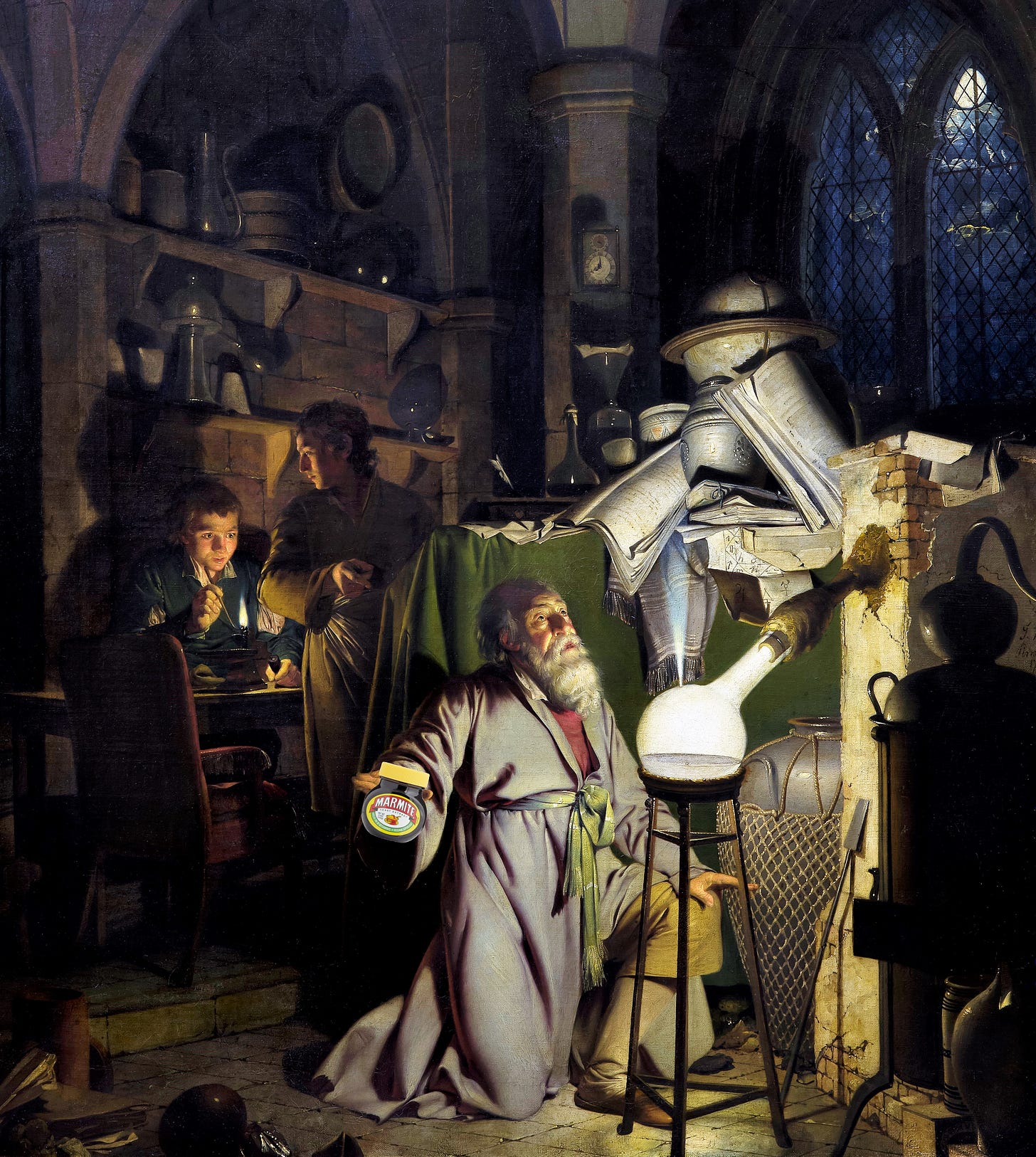

This idea of the unification of psychological parts was also the main motif of alchemy – a key influence on Jung – which was not the chimerical quest to transform lead into gold, but the religious and philosophical tradition that used this physical process as a metaphor for spiritual transformation, whereby the various “ingredients” of the self must be broken down and recast into a new, unified substance. A new you.

We can trace alchemical themes in Shakespeare’s plays, where I think they provide an insight into the mechanics of some of his dramas, and perhaps help us to account for a number of the recurring themes and patterns that commentators have identified.4 Romeo and Juliet, for example, may be seen as the tragedy of the failure to unite the “two warring houses” of body and soul (the alchemist’s “mystical marriage”). King Lear traces the soul’s path from ignorance to knowledge, as Lear’s old self (the base leaden matter) is broken down into its constituent parts (he gives his kingdom to Goneril and Regan, who represent powers of painful self-analysis and emotional turmoil), before re-emerging into a new form (the wise Lear, who has learnt – sadly, too late – from his folly and vanity, and should have known his own true worth (Cordelia – his true self) all along).

Of course, all this may be fanciful – it’s easy to read into imaginative works whatever patterns we favour. And it may be that such motifs (disintegration and reformation, warring opposites, etc.) are in-built into our acts of creation, and not any intentional act of the author. For instance, it’s interesting to note how, when writers create stories, the character list seems often to cover the spectrum of various possible “types”, as if some instinct in us is pushing us to express the whole of who we are. You tell a story, and the “hero” is often that part of yourself that unconsciously you most favour, the bit of your self that is most well adapted. But there must also be a “villain”, that part which you deny in yourself and which you “hate” or repress. And of course, there are the supporting characters, those moderately developed aspects that also help or hinder us.

But which is “me”?

All of which brings us back to Marmite. If my “resurrected” self (floating around in the Cloud, perhaps, or downloaded into a new 3D-printed body) did not like Marmite, would it still be me? Or what if it didn’t like Mick Herron books? Tastes change, obviously – and there’s no more radical change than death! But there should be some consistency, shouldn’t there? Some criterion for personal identity – a sort of “double opt-in” security procedure for the digital afterlife? If I’m to reacquire the same possessions and rights I had when I was alive, then it should involve something a bit more reliable than simply the abilit to recall the name of the street I grew up on or that of my first pet – shouldn’t it?

I don’t really know the answer to that – I think this has been more of a “Ramble” than usual. But I do think that we have evolved an overly narrow sense of self. I think the medical approach to mental health often encourages us to think of our emotions and desires as malfunctioning machinery that can be manipulated by chemicals. Whether or not they can or should be – and I’m not necessarily denying the usefulness of drugs altogether – I do think we’ve lost a greater sense of who and what we are, and of our position in the world. That this greater self lies in fragments doesn’t mean that it cannot be reassembled. In fact, rather than something we should pay attention to only when the “machine” is broken, perhaps that’s something that should form a more central goal of our lives. Perhaps even the reason for it.

[If you have suggestions for things you’d like me to write about, get in touch via Substack DM, my website, or leave a comment below.]

The Ramble represents my occasional musings on things that interest me philosophically – technology, art, science, religion, the facial hair of the great philosophers – free to everyone until the end of time (well, until the end of my time, anyway...).

See https://neurolaunch.com/brain-through-nose/.

This discussion takes place in the paper “Death” (1955) D. M. MacKinnon & Antony Flew.

See Beyond Good and Evil, Chapter 1, section 19 (towards the end).

See Charles Nicholl’s The Chemical Theatre, which is primarily about alchemy, but has chapters on Shakespeare (specifically King Lear). Also Ted Hughes’ Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, which takes a broader, mythological view. Priscilla Costello’s Shakespeare and the Stars puts the Bard’s work into the context of the contemporary belief about astrology and the medieval doctrine of the four humours – I’m not a believer in astrology, but we think of it as a sort of proto-psychology, an intuitive attempt to identify “types” of personality.

Wonderful thoughts, Gareth! -- and some day if you wish, perhaps you might muse further on "distributed" selves (or non-selves) -- e.g., Daniel Dennett's comments in FREEDOM EVOLVES:

"If you make yourself really small, you can externalize virtually everything" with footnote: "This was probably the most important sentence in Elbow Room (Dennett 1984, p. 143), and I made the stupid mistake of putting it in parentheses. I've been correcting that mistake in my work ever since, drawing out the many implications of abandoning the idea of a punctate self. Of course, what I meant to stress with my ironic formulation was the converse: You'd be surprised how much you can internalize, if you make yourself large."

and so forth ... see the random note-to-self (?!) at https://zhurnaly.com/z/No-Self,%20One-Self,%20All-Self.html with links ...

THANK YOU again for thoughtful & provocative essay, GS! 🦄